by Dafina Halili

Once, twice, maybe three times, I’d get a message from a foreign journalist.

They wanted to know if I could find them a sworn virgin.

I would stare at the screen for a while.

As if one could just walk into the street, raise a hand, and ask:

“Excuse me, is anyone here a sworn virgin?”

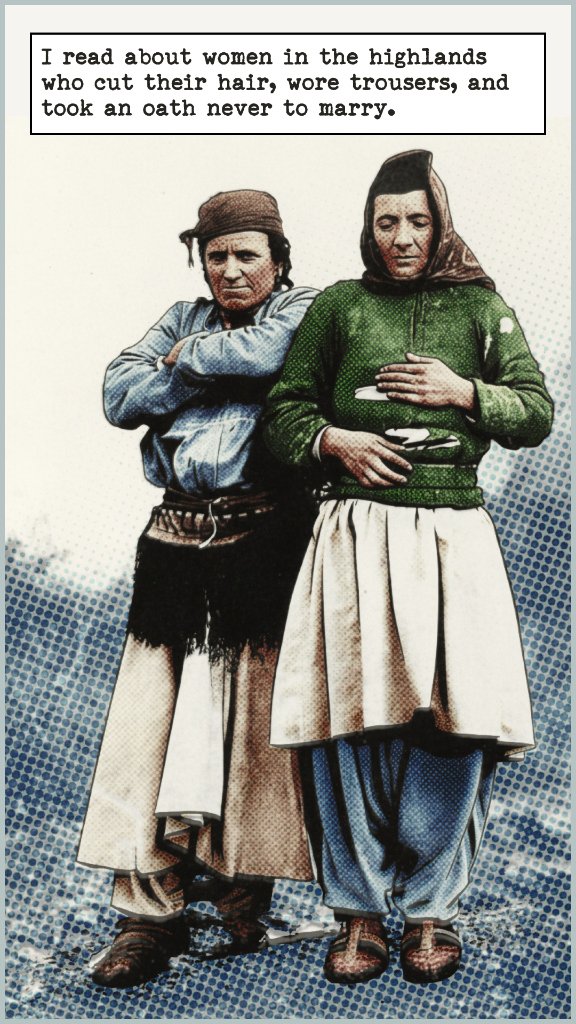

I read about women in the highlands who cut their hair, wore trousers, and took an oath never to marry.

They carried guns, plowed fields, and inherited the house.

They became “men,” in a way the patriarchy could understand.

By the time I became a journalist, there were barely any left.

More legend than reality.

I kept reading, trying to make sense of how gender is constructed in a nation I just happened to be born into.

But foreign journalists loved the idea.

For them, the sworn virgin was like an “ancient” Balkan relic, a mythical character to decorate their story.

Like finding a dragon in the mountains.

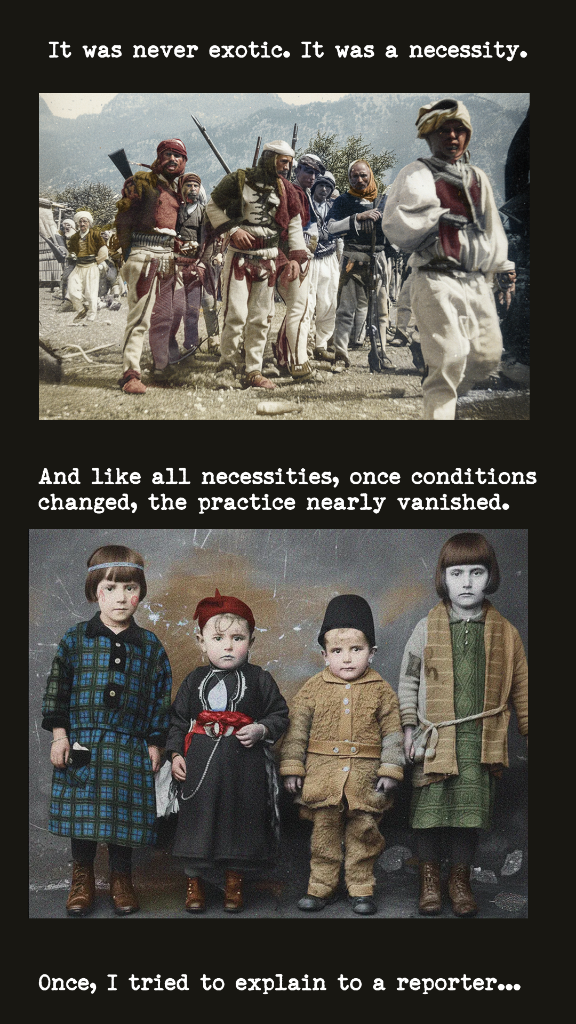

Sworn virgins are women who renounce marriage and sexuality to take on the role of men in their families.

It was a survival mechanism in a society where inheritance, honor, and labor depended on men.

It was never exotic. It was a necessity.

And like all necessities, once conditions changed, the practice nearly vanished.

But try explaining that to the ones who arrive with a camera crew and a fixation for the “last sworn virgin.”

They want the mystery, the ritual, the cinematic cut of an “ancient tribe.”

Once, I tried to explain this to a reporter.

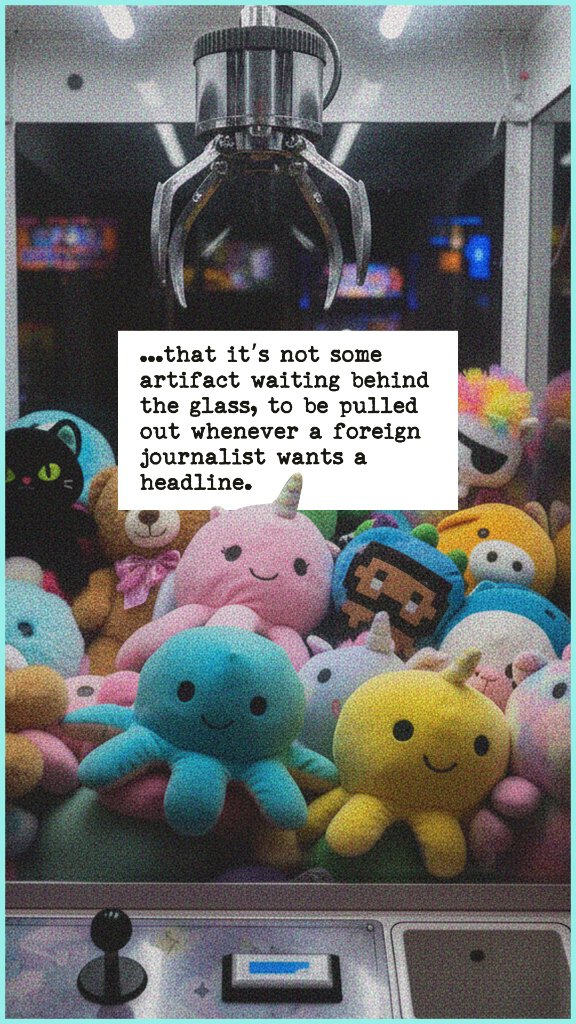

That it’s not some artifact waiting behind glass, to be pulled out whenever a foreign journalist wants a headline.

That in Kosovo today, asking for a sworn virgin is like asking if the baker still bakes with stone-age fire.

He nodded politely, then asked again:

“But do you think you could find me one?”